My last day at home

When the day came, Tom arrived early in the morning to take me to the bus in Oxnard. He said that the radio was reporting that the Allied Forces had landed on the continent of Europe. It was June 6th, 1944.

We went to Fort MacArthur, in San Pedro, to be inducted. The first order of business was haircuts all around, then uniforms issued, much paper work, aptitude testing, and all that sort of thing. It seems to me that I was there for nearly two weeks. Finally, we were given passes to go home for a couple of days before reporting in at the Union Station in Los Angeles. After emotional "goodbyes" to Barbara and Danny we were loaded onto a troop train bound for Fort Lewis, Washington. I think the trip took three days.

My last day at home

Fort Lewis is located between Olympia and Tacoma, on both sides of Highway 99, now I-5. The Main Fort was Infantry, and the North Fort, where we went, was Engineers. We were assigned to Training Companies, issued more clothing as well as rifle, helmet, gas mask, bedding, etc. The barracks were of two floors, with about fifty men on each floor. They must have been empty for a while before we moved in, because they were very dirty. The walls and open ceiling were covered with what appeared to be soot, from the coal furnace I suppose. We spent a week or more cleaning every inch of floors, walls, and ceiling. We used gallons of TSP, which was quite effective at removing skin from our hands, and somewhat effective on the soot! When we had our barracks clean we were sent over to clean the BOQ-bachelor officers quarters. When all was "shipshape", if youíll pardon the expression, we were ready to start Basic Training.

This was just what the name implies. Basic military stuff--chain of command, discipline, etiquette, marching, fitness, care and use of weapons and gas mask. I donít remember how long this period was, but six weeks minimum, maybe longer. Along the line I learned a few lessons from an older man that was in our unit. He had been in the Army a long time, and here he was taking basic training with the rookies! I did find out that he had been high up in the enlisted ranks before being busted down to private again. One can only speculate on what he may have done to bring that on himself. One day we pulled KP (Kitchen Police) together. He told me to stick with him and learn how to make an unpleasant task easier. The first thing he did was to volunteer us to wash pots and pans. As soon as breakfast was served we started on that, which got us out of keeping food on the tables, cleaning tables, mopping floors, and washing, drying and putting away the dishes and silverware. Next he told me that one of the easiest jobs was to peel potatoes. This sort of went against the grain, but he was right. We took a bag of potatoes outside, found some shade, and boxes to sit on and had a leisurely morning peeling potatoes. All that was required was to have them ready for the next meal. By the time the day was over I realized that he was rightóby choosing the jobs that seemed the hardest, we actually didnít work as hard as the others did.

Basic was followed by a similar, or longer, period of Advanced Training. This was Combat Engineer training. In addition to more advanced weapons training, we got into explosives, demolition, and some bridge construction. At the end of this session we went out into the woods on maneuvers.

A couple of incidents from that time stick in my memory. The first night out in the forest we had dug fox-holes to sleep in, then some of us were taken out to the perimeter to stand guard. By the time I was relieved it was the darkest dark I had ever experienced. No moon, no stars, no horizon, all under a canopy of trees. I wandered cautiously toward where I thought my fox-hole was, bumping into trees, falling into the wrong fox-holes. I kept working my way from one to another until finally finding my own. I always thought I had pretty fair night vision, but on that night I literally could not see my hand in front of my face.

Our next camp was in more open country. My buddy, Carl Minor, and I had just come in from some sort of patrol and were settling in under the blankets in our pup tent. I heard the telltale " click" of a grenade safety handle being released, followed by a thud just outside our tent. The "enemy" had penetrated our perimeter! (I should point out that the only grenades we were issued were either smoke or tear gasóno explosives!) The next thing we knew our tent was filling with tear gas! It turned out that the grenade had come to rest up against the tent and the gas had burned a neat hole in it. So, all the gas was being released directly into our tiny tent! I think we literally tore the tent down fighting our way out to fresh air. We spent the rest of the night coughing and wiping our eyes. It was not a fun experience! The odor of the gas stayed in our wool blankets as a reminder for weeks!

Back at the Fort some of us were assigned to Construction Foreman School. It was during this time that my cousin from Oregon, Orville Reynolds, came to my barracks to talk to me. He was an instructor at the school and had seen my name on the roster. He told me that the school was looking for more instructors. All the instructors were asked to make recommendations. If I was interested, he offered to put me on the list every week, assuring me of a job. Sure enough, at the end of the school term, I found my name on the list of instructors for the next term. I think that the only subject I taught was the use of the carpenters framing square. I have had plenty of opportunity to use what I learned about that subject! Incidentally, Orville and I were both assigned to the same Construction Battalion, went overseas together and had some contact while on Ie Shima.

I need to backtrack just a bit here. Before leaving Barbara and Danny, we had decided that it would be impractical, if not impossible, for her to follow me. Imagine my surprise a few weeks later when a letter arrived telling me to start looking for a place to live, as she and Danny were determined to come and be with me. I think that all our parents tried their best to dissuade her, but she was, then as now, a very determined lady! I was still in basic training and therefor not allowed off base at any time. That made it impossible for me to even look for a place to rent. I did let her know that there was a guesthouse for dependants available for short-term use. Barbís mother, "Mom" Wilson came along to help drive and take care of Danny. By then we had made a trade of the Ď37 Plymouth for a Ď41 Ford sedan. Needless to say, it was filled to overflowing with clothes, blankets and a folding playpen for Danny. Barbara got settled into the guesthouse, and after a day or so Mom made the return trip on the train. It sure was great to see my family again!

She found that there were a couple of other guesthouses on the Main Fort, and by moving every week she could have a place to stay until she found something more permanent. She did find a tiny house in the nearby town of Tillicum. It was new and we had to wait several weeks for it to be ready for us. By this time I had finished basic, which meant I could get a 24-hour pass. So when the day came the three of us moved into our new home. It must have been furnished, because I know we didnít buy anything for it. Looking back I marvel that Barbara, not yet twenty years old, had the nerve, courage and determination to pack up our nine month old Danny, drive 1200 miles, across three states and then find a place to live, all on her own! SUPER MOM! I am so proud of her!

We had a small bedroom, bath, kitchen and front room-dining room. The kitchen had a wood stove that also heated water for the house, as well as heating the house itself. The first order of business was to find firewood. During her stay at the guesthouses Barb had heard talk of a place on the Main Fort where we could buy wood. When we investigated, we found that there was indeed a sizable wood yard. Of course it was pine and fir, rather than the eucalyptus we were accustomed to. The least we could buy was ľ of a cord. I filled the trunk and the back seat of the car, trying to get as much as possible, but still way short of what I had paid for. When I checked out they marked on my receipt that I had more coming to me. I canít remember how many times I went back, but I never had to pay any more!

Danny, about one year old, at Tillicum

By this time the rainy season had set in, and the wood, though cured, was wet with rainwater. The system we worked out was to stack the wood in the shed where we parked the car, then move it to a box next to the stove, then into the oven (with the door open), then into the firebox!

We stayed in this little house until just before Christmas, when I got a two weeks furlough. We decided not to pay the rent while we were gone, trusting that we could find another place when we got back. We packed our things in the car and headed for Simi. We made the whole back seat area into a flat bed-playpen area for Danny. That wouldnít be allowed today, but it sure worked fine for that trip!

We took off as soon as I got off duty on a Friday evening. We took turns driving, at 35 MPH in those days! By the next morning we were in northern California, arriving in Sacramento after dark, where we stopped to eat in a restaurant. When we got back in the car the Valley fog had settled in around us. I still donít know how I found the way through Sacramento in that fog. We drove all night in the fog, finally breaking out of it on the Grapevine. I think we got to Simi in the late afternoon, exhausted. Dorothy had a nice meal for us that night, and all was well!

All too soon it was time to head north again. The return trip was more or less a repeat of our trip down, with a couple of differences. We went up the coast as far as San Francisco, to avoid the fog. Iím not positive, but I think we stopped in San Jose, at Barbaraís Grandmotherís for breakfast the first morning. Then, farther north, as we were leaving Dunsmuir, we had to stop and put on tire chains. I canít remember where we finally took them off.

We had to buy gas in the amount of our ration stamps, which meant that we could never top off the tank, which was not very big. At one stop on the way south I asked the attendant to put in five or seven gallons, whatever the stamps were. I wasnít paying attention, and by the time I looked at the pump he had already filled the tank. I thought I would have to give him another stamp for only a couple of gallons. When he found out how far we had to drive he assured me that he had extra stamps, and in fact didnít take even one stamp! For the return trip, Alan gave me some extra stamps from Sinaloa Ranch. The last night of the trip was a little worrisome. We were in Washington, after dark, and no service stations open. We finally made it to Olympia, and after much discussion with a motel owner, were able to get a room for the night.

Once again Barbara performed her magic, finding us a housekeeping room in a motel between Fort Lewis and Tacoma. Shortly after this I was assigned to the Construction Engineer Battalion that would eventually be sent overseas. I also got a "Class A" pass that allowed me to leave the Fort whenever we were off duty. This meant I could spend more time with Barbara and Danny.

Several of us from each Platoon were designated for advanced machine gun training and sent to the gunnery range near Yakima, WA. We spent several days firing .30 and .50 caliber machine guns. One day was spent firing at targets being towed by a small airplane. Luckily for us they werenít firing back at us, because our "hit" rate was mighty low!

In March we went out on a training exercise into the mountains to the east. Our Company was assigned the task of building a bridge across a stream that flowed alongside the road. Our camp was on the far side of the stream, so we were sort of isolated in the beginning. It was very cold--frost every night and occasional snow. During our stay I learned to drink coffee, as it was the only hot drink available.

As for the bridge, one group got busy building abutments of stone and cement, and the rest of us went into the woods to select and fall the trees for the girders, and others to be cut into planks by a portable sawmill. There were those among us that had experience in the forest, so that work went well. No chain saws, of course, just two man crosscut saws and axes. The girders were cut to length, barked and dragged to the bridge site. Getting them in place across the stream was the hardest part. About the time we got the first logs in place one of our "scouts" discovered a small café up the road a mile or so. Best of all, they had beef on the menu, and cheap. (We almost never got beef in the mess hall) A group of us decided to walk up there for dinner that night. We crossed the stream on one of the logs, which was no great problem, as they were at least two feet in diameter. We enjoyed a nice meal, then walked down the road toward camp. Guess what! The logs are now covered with ice. Walking on those icy logs; in the dark, twenty-five feet above the rocks below seemed a little too exciting. Some chose to wade the icy stream, I got astride one of the logs and scooted across.

Winter Dress Uniform

After returning to Fort Lewis we got the news that we would soon be shipping out, to the Pacific obviously, as the war in Europe had ended. We arranged for Dorothy to come up by train to help Barbara and Danny on the drive home to Simi. I hated to have my family leave, so I rode with them the first evening. We got a motel room in the area of Vancouver, WA. In the morning, after more emotional good-byes, they headed south and I headed north, hitchhiking. The first ride I got was from a man that turned out to be a bus driver. When he let me off, he gave me a transfer from his pocket that got me back to Fort Lewis.

We were given one more assignment before leavingótwo weeks at the firing range in Yakima, but this time to build five single story barracks and some other buildings. Barbara was determined to come up by train to be with me as long as she could, leaving Danny with his Grandmother Dorothy. When I told her on the phone about going to Yakima, she told me to find a place for her to stay, and she would meet me there. I asked one of the ladies in the Service Club in town and was directed to a private home nearby. I was able to arrange for an upstairs bedroom for her. She arrived a few days later, and we were able to spend evenings together, and one weekend. We were sort of enchanted with the little town of Yakima. The people were very friendly, and we found a nice place to eat in the downtown area. For years we talked about going back, as sort of a nostalgia trip. Well, forty years went bye before we made that return trip. Like so many small towns, Yakima had grown and was all hustle and bustle. Worst of all, our favorite eating-place was gone. So much for nostalgia!

Barbara followed me back to Fort Lewis and stayed in a guesthouse until we left. I think that it was our last day together that we went to a circus in Tacoma. Wasnít that romantic!

There were lots of wives and sweethearts on hand the next morning as we marched to the train for the trip to Fort Lawton, in Seattle, our Port of Embarkation. We were there for about a week getting shots, warm weather clothes, and whatever else we needed for the trip to?????

On June 4th, 1945 we were loaded onto our transport ship, the Acancagua. She had been built in Copenhagen, Denmark in 1938 for the Chilean government as a combination freight and passenger ship. The U.S. purchased her and she was converted to a troop transport. Our entire battalion was on board, as well as a several hundred more men from some other units. We were very crowded. Our bunks were stacked five high, with barely room to walk between rows. We were ordered to go to our assigned bunks and wait there until everyone had boarded. I was in a bottom bunk in the forward hold, portside. Finally, we were released to go up on deck, which was also very crowded. There we were able to watch as the ship made her way up the Puget Sound and the through the Juan de Fuca Straight. As the mainland faded away in back of us I think it would be safe to say that each of us had a flood of emotions-- loneliness, relief that at least we were on the last leg of the journey, and most of all apprehension about what lay ahead.

For my part, I didnít have to wait long to find out what was in store for me--I was seasick, and stayed that way for the first four of our seven day trip to Honolulu. We made this run by ourselves--no convoy, which meant that we were traveling at about eighteen knots. After Honolulu we were always in convoy, traveling at the speed of the slowest ship, about twelve knots, sometimes slower.

We stayed three or four days in Honolulu. One day we were taken by truck to a City Park and beach. I was not much impressed with what little I saw of Honolulu, and decided that it was not a place I needed to revisit later. Of course we did not see the nicer part of town, or get out into the countryside to see the scenery. The beach itself was very flat, and we had to wade out a long way to get into deeper water. And of course we were walking on coral rather than sand. It was sometimes rough and sharp. It sure didnít compare with the sand beaches of southern California!

While we were in Honolulu a small PX was opened on the ship where we could buy a few things. I laid in a goodly supply of canned tomato juice, thinking it would help me get through the next bout of seasickness. It worked pretty well. When we put to sea again I pretty much lived on tomato juice for two or three days, until my stomach got its "sea legs".

When we left Honolulu, as when we arrived, we had to pass through the anti-submarine nets stretched across the harbor entrance. As I remember it, a tugboat opened the gate long enough for us to pass through. Outside the harbor we joined a small convoy of merchant ships, escorted by several Navy submarine chasers. The Acancagua, and, I assume, all the merchant ships, had anti-aircraft guns mounted both fore and aft. Navy personnel manned these guns. Soon after we got under way some small planes flew over, towing targets. It was comforting to see that the Navy boys were much more proficient than we had been at Yakima! During the weeks ahead we had many alerts, some only drills and some real. At the first alarm we were to get dressed, put on life jackets and go up on deck. Our compartment was at the lowest level, so we were always the last ones to get topside. When there was actually a sub in the area the convoy would turn and run directly away, not to outrun the sub or torpedo, but to present a smaller target. To my knowledge there were never any torpedoes fired at us, nor evidence of subs being sunk by the depth charges that the escort ships occasionally dropped. Nevertheless, we knew the danger existed.

Somewhere west of Hawaii we crossed the International Date Line. We went to sleep June 20th, and woke up on June 22nd.

Our next landfall, if you could call it that, was Eniwetok. Eniwetok is a coral atoll rising majestically out of the blue Pacific, to at least four or five feet above high tide. There is no fresh water here. The Navy uses de-salinizing units to supply water for those stationed there. Here, as everywhere we stopped on our cruise, there were an unbelievable number of ships.

After a day or so we were off again, this time to Saipan, where we stopped for a week or so. Saipan, Tinian and Guam all had air bases for the B-29 bombers. Every morning we watched them returning to their bases after bombing runs on the home islands of Japan. They were low enough that we could see that some were damaged from combat. And of course we got news of the number that did not come back at all.

Here we saw mostly Navy, rather than merchant ships.

Our next run was short, taking us to the Ulithi Group of islands, and Mog Mog in particular. We dropped anchor in a huge lagoon, surrounded by low coral islands. To look out across the lagoon was like looking at a forest--a forest of cargo booms and smoke stacks of the hundreds of ships at anchor here. It seemed strange that everywhere we went there were dozens, or hundreds of merchant ships, not loading or unloading, just anchored. I can only assume that these ships were loaded with all the things that would be used in the invasion of the Japanese home islands. The fact that they were assembled in such large numbers would indicate that the invasion was not too far off.

We were now at the southernmost point of our little excursion, only 10 degrees north of the equator, and it was hot! We were taking salt tablets every dayóto help prevent dehydration, I guess. We also took Atabrine, to prevent Malaria. After a couple of days we were taken ashore in a landing craft for a few hours of recreation on the beach. It was too hot for sports, so I spent most of the time in the water. Beer was available in limited amounts, but no sodas or food, so I was out of luck.

The food on the ship was not very good, to say the least. The only good thing was that they had a good baker and bakery. We had good fresh baked bread every meal, but no cake or pastries. Those were reserved for our officers and the crew of the ship. Where we lined up waiting to get into the dining area happened to be right outside the dining area where the crew was served. Through the portholes we could see that their food was a whole bunch better than we were getting. The portholes were normally open because of the heat. One day as we were waiting to eat, the Filipino stewards were setting up the tables, preparing to feed the crew. They placed a platter of cake at the end of each table, directly under the open porthole. When they had gone back into the galley I reached in and brought out a platter of cake. Who knew I had so many friends! That cake disappeared in about three seconds! It didnít take long for the stewards to discover what had happened. There was lots of excited discussion with the cook and pointing in our direction, and Iím standing there with the evidence in my hand. I did what any red-blooded soldier would do---I dropped the platter over the side, into the lagoon! Needless to say, the portholes remained closed after that. Somewhere on the bottom of a lagoon in the Pacific there lies a platter with my fingerprints on it. I wonder what the statute of limitations is for cake-snatching, or worse yet, piracy on the high seas!

Life on the ship was mostly boring. A few of us started a blackjack game that went on for hours every day for weeks on end. None of us knew what we were doing, and it was strictly penny ante. Probably no more than fifteen or twenty cents changed hands in an entire day, and at the end of the trip we all came out about even. There were five of us, and no outsiders allowed. Iím sure that a good player could have cleaned us all out!

One day we were told that we were to go ashore the next day for more recreation. Two or three of my friends and I decided that we had to do something about food for the "picnic". As luck would have it, two of us were on KP that day and we had a friend that was working in the bakery. We managed to "liberate" a couple of loaves of bread and a large can of corned beef. So the next day, after a nice swim, we found some shade and made our corned beef sandwiches. Before long we had drawn a small crowd. When we had our fill, we started selling sandwiches. Needless to say, we could not meet the demand!

A few days later we awoke to find that we were moving out of the lagoon, and forming into a convoy. There were about forty ships altogether, including six destroyers and an aircraft carrier. The rest were troop ships, cargo ships and tankers. The word was out that we were headed for Okinawa and Ie Shima. Finally, on July 24th we anchored off Ie Shima and were taken to the beach on landing craft. The Acancagua had been our home for fifty-two days and I, for one, was glad to say goodbye to her! In fact, after fifty-two days, had they put us ashore in Tokyo we would still have been ready to get off that ship! Fortunately, the greatest danger we faced in the next couple of days was from the smokers who had run out of cigarettes! Some of them were downright cranky. We pitched our pup tents on the beach and had the first of several days of K-rations. The next day we were transported to our permanent location, which was just a flat area away from the beach. We "set to", putting up a long tent, later replaced by a Quonset Hut, for kitchen and dinning area. As soon as the equipment was installed in the kitchen we started getting hot meals again. We put up two rows of squad tents, each housing twelve or fourteen men. The street between the tents was surfaced with crushed coral. We also had a shower room, latrine and laundry room. Eventually, there was a chapel and a very nice Chaplain. Another priority was making air raid shelters. We dug, by hand, trenches about six feet wide, eight feet deep, and maybe twenty feet long. Timbers were placed over the top, then covered with a mound of dirt. These shelters would not have protected us against a direct hit, but they would, and did, protect against falling shrapnel.

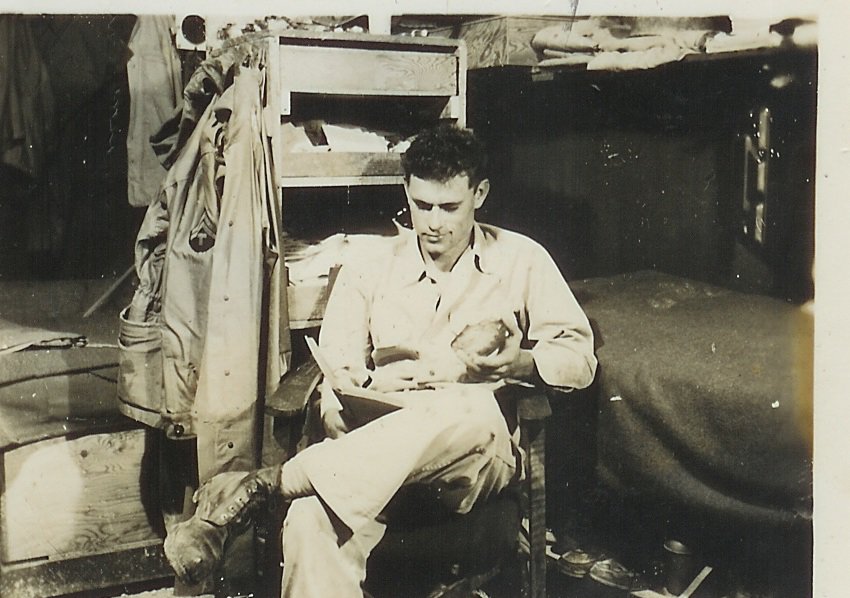

Our squad was in the closest tent on the left.

There were air raids every night, weather permitting. The bombers were targeting the air fields, harbor, fuel and ammunition dumps, which were all some distance away from us. The only way that a bomb would drop in our area was if a pilot could not reach his target and chose an alternative. Fortunately this did not happen to us. The only thing that fell onto our tent one night was a shell fragment, surely from our own Anti-Aircraft guns. We got sort of blasé about the whole thing, staying in our bunks until the AA Battery closest to us opened fire, then scampering into our shelter.

Our Mess hall

During this time we had quite a bit of rain. It would rain hard, then the sun would come out and dry us. We learned that the best way to handle it was to go shirtless, work right through the rain, get warmed by the sun, and start the cycle over again.

Our Engineer Construction Battalion (I canít remember the number) had men trained in all aspects of construction. Headquarters Co. had equipment and truck drivers, as well as all the normal functions of supply, personnel, and communications. The other companies had carpenters, plumbers, electricians and what have you. I was classified as a Heavy Duty Carpenter, with the exalted rank of T-5 (technician fifth grade--the same grade as a line corporal). It only took a few days for us to get settled into our new home, then we were sent out in various directions to work on construction projects. We assembled lots of Quonset Huts, as well as some wood frame buildings in the Island Command area. The Quonsets were completely new to us. I can remember the first one we did--the Sargent studied the instruction manual while we started opening bundles. Then he would study and give directions on each phase of the work. It didnít take long to get proficient at it--each of us sort of found our niche and did the same job over and over again.

The equipment operators were assigned to work on the construction of the airfields, runways and parking areas. This work went on around the clock. Most of the Japanese bombers came at night, but the orders were to turn off the lights and stop work only when the first bomb landed on the airstrip. All the roads and airfields were surfaced with crushed coral. It compacted well, and made an all weather surface.

Ie Shima is a rather small island, maybe five miles long and three miles wide. The first U.S. forces went ashore there on April 4th, and the island declared secure on April 20th. However, there was enemy activity right up to the time we arrived. Very few Japanese soldiers surrendered. They mostly died or hid in caves, coming out at night to attack isolated troops and gather food, even some daytime sniping. This was a pattern on most of the Pacific islands--some Japanese soldiers remaining hidden for years and years after the war had ended.

Famed war correspondent, Ernie Pyle, was killed by machine-gun fire here on April 18th 1945.

The invasion of Okinawa started on April 1st, following two weeks

of air and naval bombardment. The battle raged for eighty-two days. It turned

out to be the largest naval operation and the largest amphibious landing of

the war in the Pacific, and one of the most costly, in lives and materiel.

Okinawa and Ie Shima were much closer to the home islands of Japan than any of the other islands occupied by the Allied Forces, and they were being prepared as the staging and training area, the jumping-off place for the invasion of Japan. Our little island was home to two airfields, thirty thousand, or more, men, and probably a thousand airplanes. Itís a wonder it didnít sink into the sea! Okinawa, of course, was much, much larger, with at least three air bases that I know of, a navy base, and who knows how many men--surely a couple of hundred thousand or more. It seemed obvious that the invasion of Japan was imminent.

One day we were putting up some Quonset Huts at the hospital near our battalion area when the wind started blowing harder and harder. In a letter home I wrote that one of the men failed to let go of the corrugated steel roofing he was carrying, and he was last sighted over Manila, at 10,000 ft. A slight exaggeration, of course, but it soon became unsafe for us to work, so we went back to our area to try to secure our tents. Ours was at the windward end of the street, so we got the full force of the gale. We were fortunate enough to find a truck that we could park on the upwind side, and used it to anchor the tent ropes. By late afternoon it was pouring rain and the wind blowing harder and harder. We had a rather sleepless night, but our tent did stay up. Not all of them did! This was the first of two typhoons that we experienced that summer. The navy lost many ships off Okinawa in one of these typhoonsóthey can be pretty fierce!

Most of 3rd. Squad, Fourth Platoon, Company C, 1635th

Engineer Construction Battalion

On Aug. 6th the word went out that some sort of powerful bomb had been dropped on Japan--an atom bomb. We had no idea what that meant at the time, but I did recall something that Steve Ries had told me a few years earlier. He held a penny in his hand and said that if we knew how to release the energy of its atoms, that energy could light up the entire city of Los Angeles. Two more weeks passed and another bomb dropped before hostilities ceased.

Ie Shima

was chosen by Gen. MacArthur as the place the peace envoys from Japan would

land, on Aug. 19th, and then transfer to our transports for the balance

of the trip to Manila. This was not the actual peace treaty, but rather the

preliminary arrangements for the Occupation Forces to land in Japan. Another

two weeks would pass before the formal treaty was signed on the battleship Missouri

off Manila on Sept. 2nd, 1945. I will insert a letter I wrote describing

that day.

_____

Sunday, August 19th 1945

Dear Folks,

I donít know how long it will be until I can mail this letter. I am writing it now, while things are fresh in my mind. I have just seen what is probably the most important event in the world today. It was the arrival of the Japanese envoys on their way to Manila, to sign the preliminary peace agreement with Gen. MacArthur.

We had known for the last three days that they were going to land here. We expected them yesterday, but they were delayed, for some reason. We went to work this morning as usual, and worked until about ten. Then the word went around that the Japs were coming. We piled into trucks and drove up to the airstrip. We waited expectantly for over an hour. Finally, word went out once more that they would not arrive until 1:30 P.M, so we decided to come on back to camp and eat lunch (we had baked ham, by the way). Just before we left we watched two giant four engine transports (C-54s) circle the field and land. These were the planes that would take the Japs on to Manila.

Just as I was leaving the mess hall, the news came over the radio that the Jap planes were circling the island, and sure enough, they were! I ran to my tent, put away my mess gear, grabbed my cap and climbed on a truck.

It is about two miles to the airstrip, but we made pretty good time, because all the traffic was going the same way. As we came closer to the field, we became part of a strange procession. Directly in front and to the rear of us were two P-38s (twin engine fighter aircraft). Further on down the line there were tractors, motor graders, and in fact, most every kind of vehicle you can imagine--all loaded with G.I.s. We parked the truck about a quarter mile from the strip and ran the rest of the way. I got separated from the rest of the men, and stopped on a high spot about 75 yards from the strip. I had scarcely gotten settled when the planes started in for a landing. The planes themselves were Japanese "Betty" bombers, with two engines, bearing some resemblance to our B-26. They were painted white, with green crosses. It had been a hasty paint jobóyou could still see the red of the rising sun showing through the white. Naturally, the planes had been stripped of all armament. They were escorted by two B-25s, and I donít know how many P-38s, probably a hundred or more. The latter continued to circle the field for an hour or more, until all the excitement was over.

Japanese "Betty" Bomber

Both planes made perfect landings, rolled to the far end of the strip, turned and taxied back to our end. They parked right alongside the two large transports that had arrived earlier. They were dwarfed by comparison to our transports.

We were not permitted within a hundred yards or so of the four airplanes. There were several hundred people gathered around the planes, most likely photographers and Air Corps officers. They pretty well hid from view the events of the next few minutes. I could see various people boarding the transport, but couldnít tell much about them.

Talking Things Over

Presently they towed one of the Jap planes up a taxiway to a parking area close to where I was sitting. One of our boys pulled his truck right up to the fence, and raised the dump bed. This gave us a grandstand seat, about 15 feet off the ground. When the plane came to rest, the crew started climbing out. There were five in all, dressed in heavy flying clothes. There were two jeeps waiting to take them away. Evidently they didnít speak English, for there was much waving of hands and shrugging of shoulders. About this time two or three thousand soldiers broke through the ring of guards and started for the Japs. They didnít have any bad intentions, just curiosity, and wanting to take pictures. I know that if I had been in the place of those Japs, I would have been just a wee bit scared! At any rate, they lost no time in getting into the Jeeps and away from the mob!

Boarding a C-54 Transport

Finally, they managed to get the crowd back far enough to bring the other "Betty" over to the parking area. After a few minutes one of the C-47s warmed up itís engines and taxied onto the strip. With a mighty roar, she started down the runway. Before she got halfway down the runway, she was in the air, on her way to Manila.

It was a great show, and one I donít think I shall ever forget, for it is part of the last chapter of this war that has caused so many hardships, and so many heartbreaks. Thank God it is all over.

I wish that you would save this letter for me, or make a copy of it. What I saw today is one of the few things that I have seen, or will see, while Iím in this army that will be worth remembering.

Just as soon as I find out from the censor that it is O.K., Iíll mail this. You will probably have read about it in the newspapers, and seen it in the newsreel, but this may give you a little different slant on it.

I sure do think of you folks a lot. Maybe it wonít be too long now till I can be back with all of you again. I want to write to Barbara tonight, so Iíll end this now.

Love, Leigh

P.S. September 2nd Ie Shima.

Sorry I couldnít mail this sooner. Iíll write again in a day or two. Leigh

________

Once the war was over our thoughts naturally turned to when we might be sent home. Soon enough the army came up with a point system to determine the order of our return. It was based on total length of service, overseas service, and maybe some other things I canít recall. It was clear that I would not be leaving for quite a while!

We continued with construction work for a while, then started to dismantle some structures that were no longer needed. I think that before too long we started to find that we had a lot of leisure time. We fixed a place to play softball, and had informal games that lasted all day on Saturday. We just sort of divided into two teams and played all day long. We didnít keep score and players came and went, but the game went on! Later a more formal softball diamond was laid out and a company team formed. I played third base, and learned to really enjoy the game. We did pretty well in our games against other teams. We also organized a volley ball team. We got to thinking we were pretty good until we challenged the officers to a game. They put us in our place pretty easily!

We had an outdoor movie area as well. We got maybe two new movies a week. I remember that the movies made by Columbia Pictures got such a bad reputation that as soon as their logo came up on the screen, 80 or 90 percent of the audience got up and left! That says a lot, considering that there was nothing else to do in the evening!

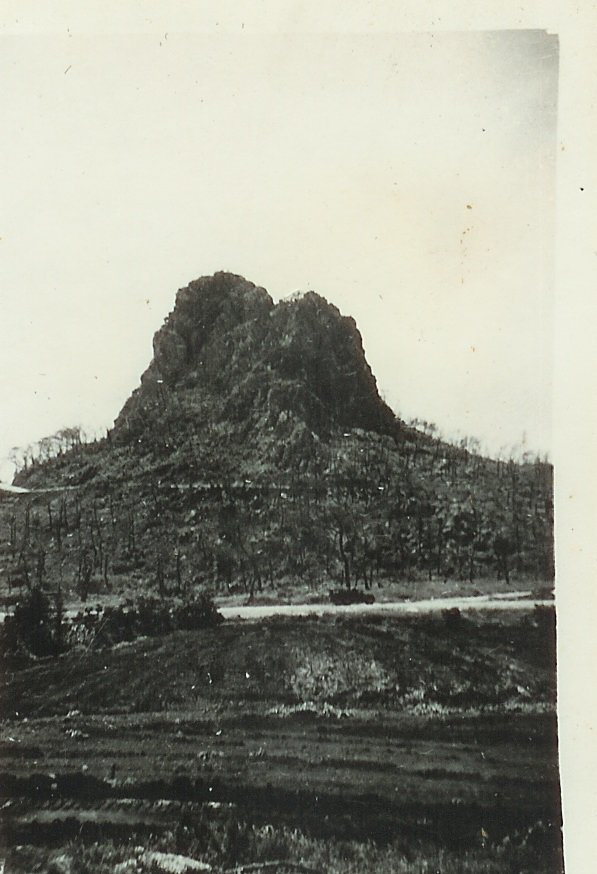

We Called This

"Devilís Pike"

Work got scarcer all the time, and boredom set in. We took some hikes up to the top of the peak in the middle of the island. It was just an easy walk, really, except for the last quarter mile. There it got rather steep and rocky. I chose not to explore any of the caves and bunkers used by the Japanese in defense of the island, but others did. We also walked over to the beach on the West side to swim and gather a few shells.

In early November a few us had an interesting adventure that is described in a letter to Barbara. It was probably not the smartest thing I ever did, but extreme boredom does tend to cloud oneís judgement!

_______

"Hardly a man is now alive who recalls the saga of Ď45".

I thought you might like to know the real story of how we won the War in the Pacific. Historians have somehow overlooked this unprecedented amphibious landing. I feel that it is time that it takes itís rightful place in history.

Now you will never have to ask the question, "Daddy, what did you do in the war?"

Monday morning

November 5, 1945

Ie Shima,

(Near Okinawa)

Hello Honey,

I'll bet I'm in the doghouse now! I haven't written to you since last Thursday. Isn't that terrible. I hope you'll forgive me. I have lots of good excuses, which I will proceed to tell you. I'll start with the last letter I wrote.

I think I told you that we were to have a basketball game Thursday evening. Well, after I finished work in the kitchen, I got a few minutes rest and then went up to the court. The game was called off for some reason, so I decided to go to the show. It was a murder mystery, "Lady On The Train", with Deanna Durbin. It was pretty good--sort of funny.

Friday, we went to work up in the Iscom area. A couple of us took the morning off to hike up on top of the mountain. I have written the folks about that jaunt, so I wonít go into detail here. You can read their letter.

Friday afternoon we got an influenza shot. I had quite a headache from it that night, so I went to bed early, without writing you. The next day I didnít feel so good either. I had a headache and my back ached--I felt just like I was getting the flu. I lay around the tent all day, and by evening I felt pretty good. Those shots really are potent--about fifty percent of the men were sick from them.

Saturday evening we saw "Dangerous Partners", with James Craig. It was a Nazi spy picture, but it was good.

Sunday morning we slept in 'til eight. Then we had fresh fried eggs--or rather egg. We also had fresh butter. It was quite a treat, but not enough of it. This breakfast was to be our last square meal for a whole day, although we didn't realize it at the time.

A couple of boys got hold of a rubber lifeboat in the dump a couple of weeks ago. They gave it a couple of test runs last week, then I helped them rig a sail on it. It wasn't much of a sail, but it was the best we could do.

There is a small island between here and Okinawa, only about a half-mile in diameter. It is about five miles from here. It is called Minna Shima. Anyway, we decided that it would be nice to do a little exploring. So, five of us set out in our little cruiser. The wind was in our favor and we flew over in about an hour and half. We had to cross a reef about 300 yards from shore. The water was only a couple of feet deep here, and there were big breakers. I was the only one that knew much about boats, so I was in the back end, steering. We let the sail down, and I picked out a spot that looked to be clear of big rocks. Our little boat rides right on the foam and we shot in just like a surfboard. Some fun! By the time we got to shore there were a half dozen native kids gathered on the beach shouting "Hey, Joe--shake hands!" We pulled our boat out on the beach and emptied the water out of it. Then we took a little tour of the island. We went in shifts, always leaving at least two men with the raft.

We walked along the beach a way then followed a path up over the sand dunes. These dunes surround the whole island, then as you go toward the middle it drops down again into a very dense jungle. The trees are only about fifteen feet high, with leaves resembling a palm. As we followed this path into the jungle we noticed other paths going off to both sides. When we investigated these we found that they led to the native huts. There we were, right in the middle of their village, and we didn't even know it. Even when we knew the houses were there we had to look twice to see them. We didn't see all of them, but there are at least twenty-five or thirty huts.

These huts are not big--only about ten or fifteen feet square. The walls are made mostly of rock. On the beach there is a peculiar formation of rock that is almost like a sheet, covering the whole beach. It is anywhere from six to twelve inches thick. They use a chisel, or some kind of tool, and cut blocks from this rock. Most of these blocks are about two feet wide and four or five feet long. It must have been quite a job transporting them from the beach to their houses. There was no machinery and no live stock on the island, so all the work must have been done by hand. The roofs are made of grass. Wooden rafters support the roof. All the woodwork is carefully jointed--showing no little skill and patience.

The farming is done on an incredibly small scale. The plots are only about thirty or forty feet square. Of course all this is done by hand, so you can't expect too much. As far as I could see, the only crops are sweet potatoes, peanuts, sugar cane, and beans. The beans are white, like our Mexican beans, only about half the size.

Some of the boys were busily trading cigarettes for seashells. A few packs of cigarettes soon returned more shells than they could have gathered themselves in a week.

About one in the afternoon we decided to head back to Ie Shima. The wind was almost directly against us. I was afraid that our makeshift sail and flat-bottom boat wouldn't sail very close into the wind--and I was right about that! We loaded into our gallant ship and paddled out to cross the reef again. This time the wind and waves were both against us and it was as much work getting out as it had been fun getting in. We rode over several breakers and got pretty wet from the spray. The next fifteen minutes were spent in paddling for all we were worth. At the end of that time we were just where we started--barely outside the breakers. Finally, we decided to try our sail. In the next thirty seconds we lost what it had taken fifteen minutes to gain. Before we could even get the sail into operation it carried us back, practically into the breakers. I saw that there was no use trying to fight it any longer, and I didn't want to get caught sideways, so I turned the nose toward shore, and off we went again, like tumble weeds in an east wind. I managed to keep her headed straight, and we came through in fine shape--just a little wet.

There had been two parties of Negro soldiers on the island, and they had the same trouble we did. So, while we were still trying to paddle out to sea, they got some natives to take them back in their canoe. That canoe just went scooting along. Our trouble was that the rubber boat was so light and stuck up out of the water so much that it caught too much wind. Anyway, we made arrangements with the kids for their dads to take us over in their canoe, but it was getting late by then, and they wanted to wait until morning. So, we prepared to spend the night on the island.

We had brought a few things to eat for our lunch. We had two K-rations, five candy bars, one can of C-ration, (lima beans and ham), two cans of peanuts and a box of cookies. We ate the K and C rations in the afternoon, as soon as we came back to the island the second time. We packed everything into the boat--the paddles and sail, etc, then carried the boat up behind some bushes, high on the bank. We were a little concerned about the kids stealing our paddles, because they seemed to look at them rather fondly. There wasn't anything we could do but leave them there, so we took a chance on it. We were very surprised to find everything in it's place when we returned for the boat this morning. By the time we got the boat tended to and went back to the village it was getting chilly, and our clothes were still a little damp. So, the kids built us a fire. Soon we had sweet potatoes buried in the ashes, roasting, and peanuts toasting on the coals. They brought us sugar cane to eat, too. We had five canteens full of water, so we didn't have to take any' chances with their water.

About this time, (6:30 or so), some more kids ran up and said there were more soldiers on the beach. We went down to see who it was, and lo and behold--it turned out to be two more boys from C Company. They have a small boat that they made themselves, with an engine from a Jap jeep in it. They had been over to Okie, and on their way back the motor conked out. The wind was too strong for them to paddle against, so they drifted down to our island. They were pretty scared. It was already getting dark, and if they had missed the island, they would have been headed for the open sea. One of them couldn't even swim. Reason enough, then, to be scared.

They were very surprised and glad to see us. We took them up to our camp. When we got there our sweet potatoes were done and we had supper around the fire, and ate peanuts and visited with the kids until about eight. The kids are very friendly, especially if you have some cigarettes or candy. They have learned quite a few words from the G.I.s. Naturally, among the first words they learn are profane--all directed against Tojo, (Prime Minister of Japan)! They want it definitely understood that they are Okinawan, not Jap. They're really pretty smart. We would ask their names, then write it out as close as we could in English in the sand. Then they would erase it and write it themselves. They sure caught on quick. Probably a lot quicker than I could learn to write my name in Japanese.

All we saw on the island were kids and men. From what we could gather, the women live on Okie. I think they work in a laundry, or something, there. Anyway, we didn't see any, except one real old lady. She looked like the oldest women I have ever seen.

The men didn't visit with us much. They just smiled and saluted! I have an idea that they don't feel any too friendly toward us, even though they are afraid to show it. You can't blame them. They lived a peaceful life here, with little contact with the rest of the world. They don't know what the war is all about. It's only natural that they should dislike someone coming in and destroying their homes, tearing up their fields. Of course it isnít our fault, either. The Japs forced us to fight that way.

Anyway, when we started getting sleepy we asked if they could get us some blankets. We knew they all had G.I. blankets, and the Negroes had given them about 3 dozen more for taking them home. The boys said they could get blankets, but on one condition--they had to sleep with us! I didn't relish the idea, but there wasn't any way out. So we got some bean-straw for a mattress, put one blanket down and one over us. My boy was very small, about ten years old, but they are very small people anyway. His name was Hagi, or something like that. He slept sound all night, but I couldn't keep warm. I'd sleep for an hour or two, then get up and sit by the fire for an hour, till I got warm and sleepy, then back to bed. I got up three different times that way. You can imagine just about how much sleep I got. Once I woke up and a bunch of them were singing the weirdest music I've ever heard. They had a little homemade banjo affair that gave vent to some very mournful sounds. They sang some of their own songs in a sing-song tone--just like Japanese. Then they started making up their own words to the tune of "Glory, Glory, Hallelujah". I can't remember the name of the song, but you know which one I mean. It was funny to hear them singing an American tune in their own sing-song way. They like to sing. Lots of them can sing American songs in English--sort of. The favorites are "You Are My Sunshine", "Shoe, Shoe Baby", and "God Bless America"

We got up early this morning and had some more sweet potatoes for breakfast. When we left for the beach, I gave Hagi my pocketknife for letting me use his blankets, even if they didn't keep me warm! He was pretty happy about that. It took about a half an hour to get the engine started this morning, but we did, finally. The wind had died during the early morning, and it was pretty quiet when we started out. The other two guys were towing our life raft. As we got about half way back here, the wind came up again, and it started getting rough. The little engine performed nobly, however, and kept running.

As we approached Ie, an LST came out to meet us. They offered us a ride back to Ie, so we went aboard. We had made the hardest part of the trip by ourselves--another half- hour and we would have made dry land. Nevertheless, we did not turn down a lift.

The captain said he had seen us in his binoculars and thought we were in trouble, so he came out to investigate. He was having breakfast, and he took us below with him for some hot coffee and bread, butter, and jam. After he finished eating he took us on into shore. The other two guys were so disgusted with their boat that they gave it to one of the sailors. That was the second time it had taken them someplace and not brought them back. I think they've had enough of the sea for awhile.

When we got to shore, Sgt. Krugerman was waiting for us on the docks! He had seen us coming, so he came to meet us. It seems as though we caused a lot of excitement! They missed us last night and tried to get a boat to search for us. The Colonel was told that the Navy wouldn't go out at night, so they waited 'till this morning.

As I was getting on the truck, the Port Commander came up and asked if we were the five men who had been missing since yesterday evening. I told him we were, and he said that some of our officers had gone out to look for us. Sure enough--there were two Higgins boats over by our island. Somehow we had passed each other without knowing it. It must have been while we were on board the LST. The Port Commander tried to signal to them, but they couldn't read the blinker signal, so they didn't get back 'till about eleven this morning. I think they had one of those Catalina flying boats out looking for us, too. We saw it, but they didn't seem to see us.

That's one way to get people to notice you--even the Colonel heard about it. It seems like everyone was worried about us except us. We were perfectly safe all the time, but we had no way of letting them know we were all right.

All's well that ends well, though, and so far none of the officers have said anything about it, except jokingly. As soon as I got back here I had a nice long shower.

Its nightime now. I've even been to a show since I started writing this letter. It was "Sunday Dinner For a Soldier", with Anne Baxter and John Hodiack. I liked it a lot.

I'm very sleepy now, Honey, so I think I'll go to bed.

All my love,

Leigh________

We celebrated Christmas as best we could in our tent with gifts from home and makeshift decorations. I think we even had a little tree of some kind.

By then a few of the older men were being sent home. Sometime after the first of the year 1946, the rest of us were taken to Okinawa, where we were sent hither and yon to replace the men who had been sent home. A large group of us joined an Engineer Depot Company stationed on the outskirts of the city of Naha. The word "city" does not really apply here. Our encampment was on the side of a hill overlooking what had been the city. Below and to our right stood a two-story concrete building that had housed the University of Naha. It was one of the very few that had survived the bombs and artillery shells. The rest of the city was, literally, a ghost town. All the native population had been relocated to the southern and northern ends of the island. Our immediate task was to erect several large storage buildings. These were of conventional wood frame and truss construction. For this chore we were assigned a group of POWs, maybe fifteen or twenty, under the watchful eyes of their guards. I canít recall, but we must have had an interpreter or two to direct their activities. These warehouses were for the collection, sorting and storage of all sorts construction tools and supplies. Besides the buildings, there was lots of stuff stored outside--lumber and tires that I remember, and surely other things.

After a few weeks Sgt. Stein was assigned the task of surveying and mapping the entire depot area. He asked a good friend of mine, Carl Minor, and me to "pull chain" for him. In plain language that entails handling both ends of a three hundred-foot steel tape. I had done this for a surveyor on Sinaloa Ranch on more than one occasion, and Carl had worked in construction before entering the army, so he also understood the job. We jumped at the chance! This also meant we would transfer to Headquarters Co. and move out of the tent and into the concrete building at the bottom of the hill. An added bonus that we didnít expect was that the food was much better. In fact it was by far the best that I had in two years in the Army. We had plenty of meat, good bread, and all the food well prepared. We also had an ice cream machine that gave us soft ice cream nearly every day.

I had learned that the quality of food varied widely from one unit to another. This all had to do with the ability and imagination of the Mess Sgt. and, or, the mess officer. In this case we had a very aggressive trader as Mess Sgt. He traded supplies from the Engineer Depot for food items, and ice cream makers, from other units all over the island, particularly the Navy.

There was, and probably still is, a whole sub-culture in the military, a sort of under-ground economy, based mostly on barter. Everything being bartered belonged to the military of course, but understandably loose inventory control made the system work. Those who knew how to work the system seemed to be able to acquire nearly anything they wanted.

Our little survey crew had a truck and driver assigned to us from the Motor Pool. The driver would pick us up every morning to take us to the job. We measured and mapped the perimeter and all the interior roads and storage areas. None of what we were doing was really very urgent, so once in a while Sgt. Stein would get the driver to take us on a sightseeing tour. We explored the island as far south as military personnel were allowed--that portion of the island being reserved mainly for the native population. We were able to drive around more on the northern end where there were both military and civilian areas. Some of that part of Okinawa was mountainous, and quite scenic.

Finally, in late April, I got orders to report to another base, in preparation for the return trip to the good old U.S of A. After a few days we were loaded onto another of those luxury liners for the trip to San Francisco. The Marine Fox, like the Acancagua, had been converted for use as a troop transport. She was a little larger, I think, and faster, and not nearly so crowded inside. There were only a handful of men that I knew on the ship, and none in my compartment. Naturally, I got seasick as soon as we got into the open sea. I spent my time between the head and my bunk. As the days went by I got weaker and weaker. I knew that I needed to eat, even if I couldnít keep it down. The problem was that the chow line was so long that I would get weak and woozy before I got to the food, and have to hit the head again. On the third or fourth day one of my friends came by, and I got him to bring me a little something to eat. Soon after that I happened to find the chow line very short, and was able to get into the mess hall and eat. From then on I was OK.

On both ships we had only salt water for showers and shaving, which doesnít really leave one feeling very clean. During the second week of the return trip I was assigned to guard duty in the middle of the night. Please do not ask why it was necessary to have guards all over the ship, and what, or whom, we were guarding against! The basic rule for an enlisted man is "If it moves, salute it, if it doesnít move, pick it up, if you canít pick it up, paint it". Now, this ship was both moving and too big to pick up, so I guess the only thing left was to guard it! Anyway, one of my posts was a companionway near the crewsí quarters. I found that their head was not being used at all in the wee hours, so I started taking my razor and a towel with me, under my jacket. Then, when all was quiet, I had a leisurely, hot, fresh water shower! Little by little we learn!

We took the northern circle route to get to San Francisco, which meant heading northeast, past Japan, toward the Aleutian Islands, then swinging slowly southward to San Francisco. It was pretty cold up on deck at night, but the fresh air was worth it. The trip that took 52 days going out was done in 14 coming home. Our first landfall turned out to be the Farallon Islands northwest of San Francisco. Soon the Golden Bate Bridge loomed up out of the fog off the port side. So many men crowded over to that side that the ship took on a very pronounced list to port. The Captain came on the horn and told us that if we did not spread out to both sides he would have to order us below. That sure reminded me of Dad Robertsonís admonition to his grandchildren when we were in one of his boatsó"trim the ship!" We knew that meant to distribute our weight so that the boat was level in the water. Well, we did trim the ship sufficiently to stay on deck as we passed under the bridge, thus completing our journey. I was not the sentimental man that I am now, but that was a rather emotional experience.

We debarked at a Navy facility near the Golden Gate, then sent by ferry across the bay to Camp Knight in Oakland. All new arrivals were given a ticket good for a steak dinner with all the trimmings in the mess hall that evening. That was quite a treat! We were also given a list of clothing and equipment that we would be allowed to keep, as well as a list of things we were required to turn in, when we were discharged at Camp Beale. It was also casually mentioned that the camp Post office would be open all night, and that cardboard boxes were available there. Well, as you can imagine, the PO did a brisk business that night! We sent home extra blankets and anything else that was extra, and not required.

The next day we were bussed to Camp Beale, north of Sacramento. There we were "processed". That meant getting all our service records up to date, collecting whatever service ribbons we were entitled to, turning in equipment such as helmet, ammunition belt, canteen, canteen cover and mess kit. Also rifle, bayonet and gas mask. Clothing we keptówhat we wanted of it anyway. We were told that anything issued to us and not returned would be taken out of our pay, but I doubt that that was enforced for the smaller stuff. Finally, we collected our last pay. Paydays were rather irregular overseas; they just happened whenever a finance officer happened to come around, so most of us had back pay coming to us. We also got transportation money to get us to our homes, and the first installment of a three hundred-dollar separation bonus.

On the afternoon of May 14th, 1946, I got my discharge papers and walked out of Camp Beale a civilian again, though still in uniform. We caught a bus into Sacramento and checked the train schedule. It would have meant sitting up all night, so two of us rented a hotel room and flew down early the next morning on a surplus DC-3 that some retired Air Force pilots had purchased to start an airline. I think that modest beginning became Pacific Southwest Airlines. We landed in Burbank about 10:00 AM, and there was Barbara and Danny to greet me. Boy, was I glad to see them! Danny, now 2 Ĺ years old, had grown so much. Barbara had been showing him pictures, so he didnít hesitate to come to me. I had requested tamale pie and fruit salad for my first meal at home, and Dorothy fixed those for me that evening. I was with my family, and all was well with the world!

I really did not like any part of being in the Army. However, Iím glad I went. We are all the sum total of our life experiences, and I did some crazy things that I would not otherwise have done. And I came away with a little useful knowledge, so the time was not a total waste.

I had contact with my friend, Carl Minor, for many years-- in fact he helped me with the project of putting an addition onto the house in Chula Vista. I saw another friend, Charles Wheeler, a few times also.

It sure is a small world. I didnít know it at the time, but one of my classmates, Ralph Chamberlain, was on an aircraft carrier stationed off Okinawa at the time that I was on Ie Shima. My future brother-in-law, John Wilson, was on Ie Shima, in the Air Force, at the same time. Also a neighbor here in Mariposa was there on Ie when I was. Probably other friends as well that Iím not aware of.